The Cluttered Desk Experiment

An article by Harvard Business Review HBR, by Boyoun (Grace) Chae and Rui (Juliet) Zhu

The disorganized accumulation of papers and coffee cups scattered across your desk may help you project the impression that you’re working at full throttle, but in fact it’s probably dragging you down. We’ve found that people sitting at messy desks are less efficient, less persistent, and more frustrated and weary than those at neat desks.

But wait, you may say. No one who has worked in a busy office for more than a week can possibly keep a neat desk — the work comes at you too fast. Or you may say that you like your mess, that it’s as comforting as a little nest. To which we say yes, it can be challenging to keep a desk neat. And yes, a mess can be comforting, even freeing, in a sense: You don’t have to worry about things becoming disordered, because they’re already disordered.

But look at the data:

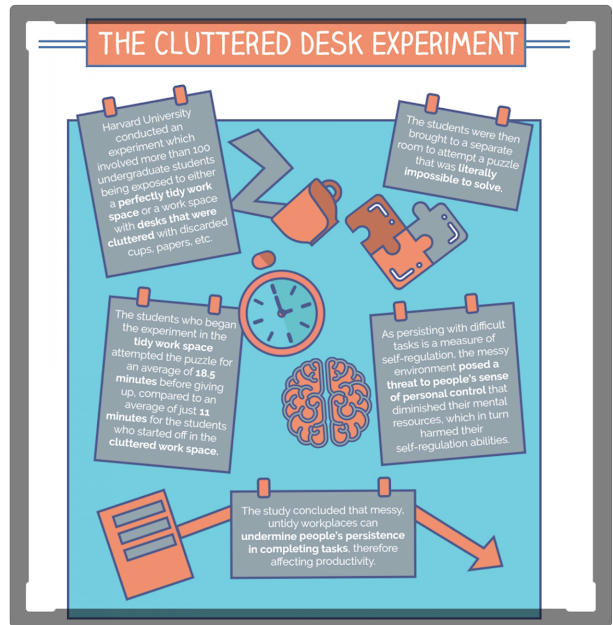

In one of our experiments, more than 100 undergraduates were exposed either to an uncluttered space or to a work area where papers, folders, and cups were scattered over shelves, a desk, and the floor, like so:

Then, in a separate room, they were asked to undertake what was described as a “challenging” — actually, it was unsolvable — a task that consisted of tracing a geometric figure without retracing any lines or lifting the pencil from the paper. Those who had been exposed to the neat environment stuck with the task for an average of 1,117 seconds before giving up, more than 1.5 times as long as those who had been exposed to the messy space (669 seconds). Other experiments produced similar results.

Persistence in a frustrating task is a classic measure of what’s known as self-regulation, which is essentially your ability to direct yourself to do something you know you should do. Self-regulation can be undermined by the depletion of mental resources, and that’s exactly what we think was going on. The mess posed a threat, in a sense: It threatened participants’ sense of personal control. Coping with that threat from the physical environment caused a depletion of their mental resources, which in turn led to self-regulatory failure.

So even though it can be comforting to relax in your mess, a disorganized environment can be a real obstacle when you try to do something.

And although we don’t have data to back this up, we conjecture that a mess of your own creation may affect you even more strongly than a mess that’s been imposed by someone else. A self-created mess can become overwhelming because it serves as evidence that you’re unable to control your environment.

We’re aware that other researchers have found there’s a benefit to a disordered environment: It seems to help people break from convention and be more creative. A team led by Kathleen D. Vohs of the University of Minnesota found that people in a room where papers were scattered on a table and the floor came up with five times more highly creative ideas for new uses of ping-pong balls than those in a room where papers and markers were neatly arranged.

The two sets of findings aren’t necessarily contradictory. In fact, it could be that the depletion effect of disorder caused people to engage in primarily affective or divergent thinking, which enhanced creativity.

In any case, our research has made us think about other factors at work that may deplete employees’ mental resources and therefore undermine their self-regulation and persistence. One possibility that comes to mind is extreme self-consciousness — ruminating about others’ perceptions. Employees might find it depleting to wonder: What do people think of me? Of my work quality? Of my appearance? It’s very possible that this kind of thinking hurts performance.

It can be challenging to turn off rumination. In comparison, solving the messy-environment problem is relatively easy. Because of our research, both of us have become more aware of the value of an ordered environment. We both keep our desks neat, and one of us (Chae) makes sure to maintain an orderly home. The reasoning: A neat environment at home allows her to head into work on Monday morning feeling fresh and restored.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your opinion! It's very important to us!